Tony Hawk is a celebrity, a champion, a brand and a video game, but most of all he is an icon. In the following interview, he talks about his sense of style and his business sense, which are closely linked.

By Raphaël Malkin.

Article originally published in L'Etiquette issue 5.

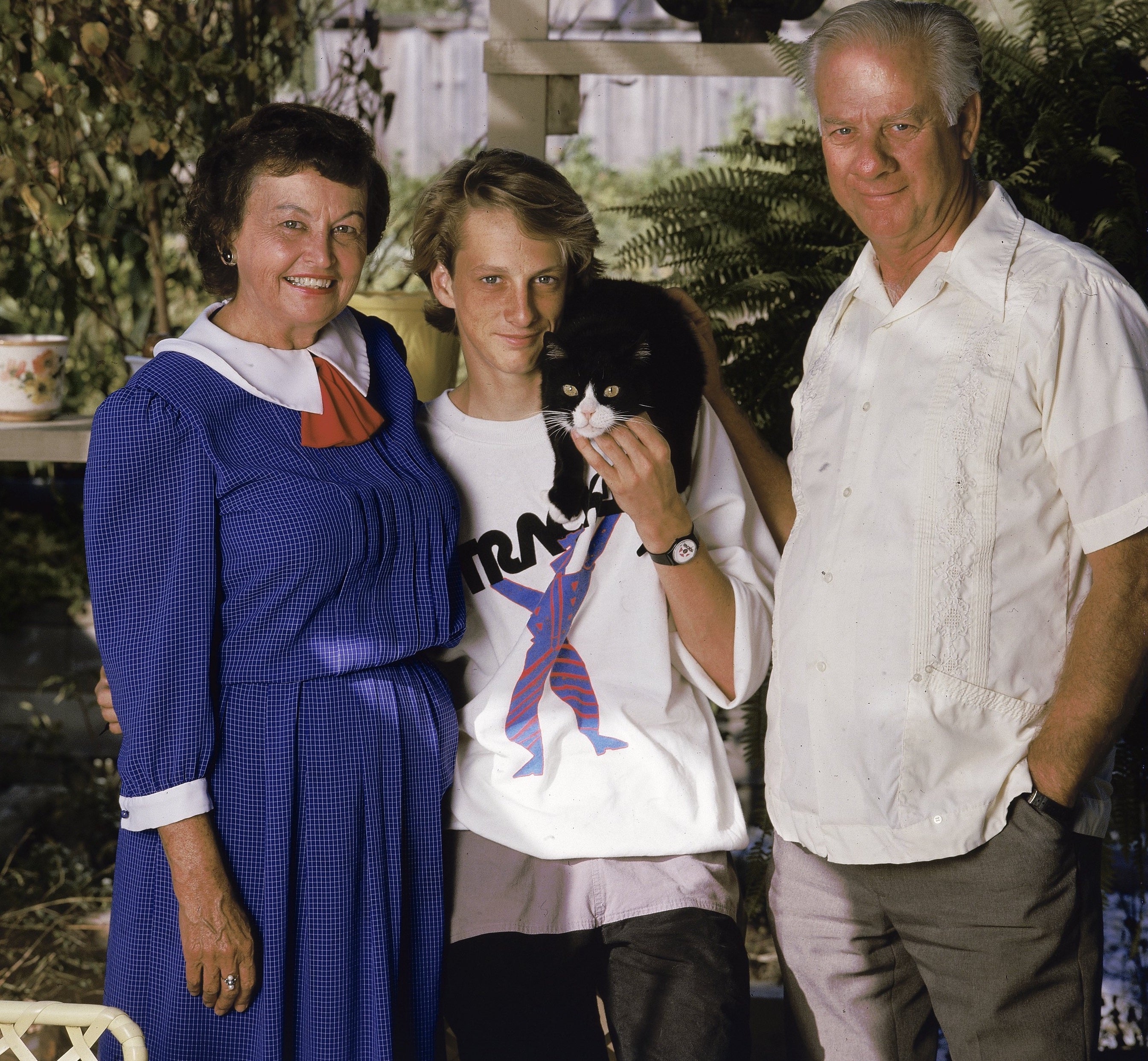

One day when he was 11, Tony Hawk jumped onto a skateboard and rode the ramp at the Oasis Skatepark in San Diego. Three years later, that nice kid with big bright eyes and long blond curls became a pro skateboarder for the Bones Brigade, a famous team known for skating in empty swimming pools. Now that Hawk is 54 years old, listing his achievements in skating is a job and a half. At the age of 25, he already had 72 victories on the circuit, 12 of which were consecutive National Skateboard Association world championships. He was also the first skateboarder to complete the extraordinary “900” trick, two-and-a-half revolutions in mid-air. But more than anything, the Californian skateboarder was the first to go beyond the sport to become a star in his own right and, incidentally, a franchise.

Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater video game, adored by skateboard fans and outsiders alike, was released 20 years ago. Its sales have brought in some $1.5 billion, and the number of licenses has multiplied. Tony Hawk T-shirts, Tony Hawk shirts and even Tony Hawk shoes are sold everywhere in the United States, from specialty shops to Walmart stores. Last year, like the brands Supreme and Palace (both of which started out in the skating world and evolved into the fashion world), Hawk decided to launch another label. Will it succeed? It doesn’t really matter because at this stage, nothing will lower the status of the man whom Tommy Guerrero, another skatepark legend, once called “the Michael Jordan of skateboarding.”

L’ÉTIQUETTE. How many pairs of sneakers do you think you’ve destroyed while skating?

TONY HAWK. For years, I have been throwing away two pairs of shoes a month. That must be something like 700 pairs.

É. What about pants?

T.H. At the start of my career, I skated a lot in jeans, very wide ones that I wore only for skating. I must have destroyed a few hundred of them. Usually, they would tear at the knees, but, frankly, it didn’t bother me. Actually, I al- ways liked those scars on the clothes. When you skate, you know you’re going to fall and tear your clothes. All the better. Sometimes I would dress all in white on purpose so that my outfit would end up gray or black with dirt by the end of the day. Ripping your clothes is part of the process when you skate; it even feels like a medal for a skater. In school, my shoes always had holes in them. My friends would tell me to buy new ones, but I refused because I wore them like trophies. Today, my youngest son is the same; he has an old black T-shirt with holes all over the shoulders in his closet. It reminds him of all his struggles on the board.

É. How did you dress when you first started skating?

T.H. I remember wearing long patterned T-shirts in summer and plaid flannel shirts in winter. At the time, I really liked the brand Lightning Bolt (that was its logo), which has pretty much disappeared today. But what I remember most about those days is the shoes. When I was 12, I picked up my first skateboard magazine, and when I opened it, I came across an advertisement for Vans, with many pairs lined up along the edge of a pool. From what I recall, there were three different models – no names, just reference numbers. No. 36 was Old Skool, 37 Sk8-Hi and 95 Era. I think that was it. The slogan was “Off The Wall.” I thought it was incredible. They were real skate shoes, nothing like the canvas Keds sneakers my dad bought me at Kmart. There were already a few brands that specialized in skate shoes, but when I saw this magazine ad, I absolutely had to have Vans. I bugged my father big time, and he agreed to pay for them. They were available through mail order with a form in the magazine, but he took me to the only Vans store in San Diego instead.

É. What style did you go for?

T.H. The classic model, Era, in blue and red, for $20. They were the ones I’d seen big skating stars like Tony Alva and Stacy Peralta wearing. My father also bought me “ankle guards” to protect my feet. In high school, everyone knew I was skating because of them. I looked like a surfer because I had bleached hair and was wearing tie-dye T-shirts, but I really didn’t want anyone to think I was a surfer, and the ankle guards identified me as a skater.

É. Do you think it was cooler to be a skater then?

T.H. Not for everyone. [Laughs] In high school, girls liked the skater style, but guys often bugged me because of the way I looked. They’d say, “You skating faggot!” I didn’t care. Thanks to skating, I knew my place in the world.`

É. In the mid-1980s, brands realized the value of being identified with skaters, and you started getting free shoes...

T.H. Yes, exactly. I actually remember the very first pair of free Vans I received. I was supposed to pick them up at the Vans store in Encinitas, near San Diego. I went there with another skater, but they refused to give us the shoes because our names weren’t on the list. We went back the next day, and they gave them to us. I think they were high tops.

É. From a technical point of view, was it differ- ent skating in Vans compared with ordinary sneakers?

T.H. Those high-top Vans in particular were really weird. I practically had to learn to skate all over again when I first started wearing them. They hugged the board a lot, much more than I’d experienced before. They changed a lot of things: the way I placed my feet, managed my body weight and turned the shoe. The problem was that I was always changing my shoes at that time. I had the Vans, but also skated with Air Jordans and Pumas. Puma had sent me a pair, saying they would like to sponsor me. I was up for it, but it never happened. It was still the age of amateurs in skating. Brands were sending us shoes, but there was no money in the business. It was a difficult time for me. I was broke. I had to leave the house I was living in and move into an apartment with my wife and son. I remember rummaging under the carpets of my Honda, hoping to find enough change to buy a sandwich at Taco Bell. Every once in a while, I made $100 doing demos at amuse- ment parks, and the rest of the time I worked as an editor for a production company. Luckily, I was picking up free clothes from the surf brand Rusty. They gave me chinos and T-shirts to keep me presentable.

É. You eventually signed a contract with a new California sneaker brand, Airwalk, right?

T.H. Yes. It was a really tiny contract from a financial point of view, but it was very exciting. It was something new, a brand of shoes just for skating. At the time, Vans was doing a lot of other things. The first pair of Airwalk shoes I wore were canvas high tops, similar to Converse All Stars. I liked the Converses; I’d skated in them in the past, so the design suited me very well. The only difference was that there was a drawing of a pterodactyl on the side of the shoe. They were certainly creative...

É. Did you tell them what you thought?

T.H. When people told Airwalk that a model was ugly, they said it was my idea. [Laughs] But, frankly, no, they didn’t need my opinion on their designs. I only had one request: I wanted dark colors – not bright – because I’m a size 47.5, and I look like a clown with colorful shoes.

É. Have you ever had trouble finding sneakers in your size?

T.H. Yes, it’s been a problem many times. I remember one time in particular, when I was working on an Airwalk ad, they only had prototypes in size 45. It was torture. Between photos, I would take them off as soon as I could.

É. In 1995, Airwalk launched a collection under your name: The Tony Hawk Series.

T.H. I was amazed at the time because I was already considered old hat. The type of skating I was doing (vertical skating or skatepark skating) was no longer as popular as street skating, which is more spectacular. But I was very proud. I wanted it to be perfect because it had my name on it. I asked for the front to be well reinforced. I also wanted a really strong ollie patch [extra protection on the side for the ollie trick]. But the most important thing for me was protection for the laces so they wouldn’t fray. No one had ever done that before, but I really wanted it.

É. How did that idea come up?

T.H. It was actually something that my dad, Frank, did. When I was skating as a kid, I used to break my laces and scrape my toes all the time. It was very painful. For a few years, I even wrapped my shoes in heavy tape. I’d also use a special transparent glue, Shoe Goo. Then my father had the idea of making leather patches. He’d glue Velcro onto them, and I’d attach them to my shoes. The leather patch went all the way down to the front, protecting my laces and my toes. It was rustic but very effective.

É. It has been widely reported that Nike also made you a huge contract offer at that time.

T.H. Nike and I danced around each other a lot. I went to meet them in Portland several times. It seemed obvious that they were wondering if they should invest big-time in skating as they did for basketball, but in the end, they never offered me a contract.

É. But it was at that time, the end of the 1990s, that skating became a phenomenon, and then an industry.

T.H. At the end of the ’80s, there were already some overtures. The Beastie Boys wore Bones Brigade (our team) T-shirts, for example. Later, underground skateboard brands started appearing in MTV videos. Ten years later, it went totally crazy. My video game, Tony Hawk’s Pro Skateboarding, was released in 1999 and was an instant hit. A few months before, I’d launched a clothing brand for young people. With the release of the game, it suddenly took off, but I couldn’t afford to develop the brand on my own, so I ended up selling it to Quiksilver, while continuing to design for the brand. Even though I didn’t own it any- more, I didn’t feel like my name was being exploited. Our idea was to make good-quality skate clothing at prices that as many people as possible could afford. We had a great pair of skate shoes, which were very solid and inexpensive. They were a big hit. I was proud of the democratic side of our products.

É. Did you often see people wearing your clothes or shoes?

T.H. Very often, even in Paris. One day, I came across an American family in a chic part of town. The son was wearing a Tony Hawk T-shirt, so I went over to say hello. He just stared at me he had no idea who I was. A few years later, I went to a gala dinner at Disneyland. Sitting next to me were Jack Nicholson and his son Ray, who was wearing a Tony Hawk Clothing T-shirt. He had never skated in his life, and again, he didn’t know who I was.

É. Jake Phelps, the founder of the famous skating magazine Thrasher, once said of you: “ He’s the man who skates with a wallet in his back pocket and a Lexus in the parking lot.”

T.H. Well, he didn’t say that by chance. In the early 1990s, I had my wallet stolen twice from my bag while I was skating on a ramp, so I decided to always keep my wallet with me while I was skating, in the back pocket of my pants. It was pretty fat and was the only thing you could see when I was skating.

É. But the sentence obviously had a double meaning.

T.H. Of course. He also meant that I have a business sense, and he’s not wrong. I’ve always managed to do business with skating.

É. Do you agree that you’re one of those who transformed – some say “perverted” – skating into an industry?

T.H. I do. I’ve never been the keeper of the temple. When I was a kid, I couldn’t understand why other boys my age didn’t think skating was cool. At my level, I always tried to get a bigger audience for skating. When Quiksilver bought my brand, my clothes ended up in Walmart stores all over America, and I was thrilled. I thought it was really cool that my clothes were widely distributed and that a lot of people – even non-skaters – wore them. I wasn’t at all snobby about it, as some skaters are.

É. So how do you react when a brand like Supreme collaborates with Louis Vuitton, or when an ordinary clothing brand slips skateboards into its lookbooks?

T.H. When it’s done well, I think it’s great. I never thought that skating and its aesthetic should belong to a small group of untouch- able, incorruptible purists. I think just the opposite.

É. Have you ever tried to dress fashionably yourself ?

T.H. Several times, fashion magazines have asked me to wear improbable clothes: country club clothes or yacht wear. See what I mean? Open-collared shirts or short, narrow, colorful Bermudas. The type of clothes a guy named Chad would wear. Luckily, I always managed to dodge those requests. [Laughs]. But I have to admit that I did have a bit of a weird suit period in the early 2000s; I was trying to look like the guys I was doing business with. I wore Zegna or Prada suits and pointy Ferragamo shoes. It didn’t take long before I realized how ridiculous I looked. My body was not at all comfortable in those clothes. I got rid of them all at once. I only have one suit left: a black Armani to wear to weddings.

É. Today, at 54, what do you wear every day?

T.H. I no longer wear prints, and I no longer wear caps, but I still look like a skateboarder – simply because I still skate. I even go to business meeting in skating outfits.

É. Those business people you meet must be happy to see the real Tony Hawk.

T.H. That’s what I tell myself, but there was one difficult meeting with the president of AOL. I was wearing shorts, sneakers and no socks. The guy flinched. He never signed the contract.