British actor Daniel Day-Lewis has always paid fanatical attention to detail when it comes to his costumes, an obsession driven by his love of acting and passion for clothes.

By Gino Delmas.

Translation from French by Helene Tammik.

Article originally published in L'Etiquette issue 6.

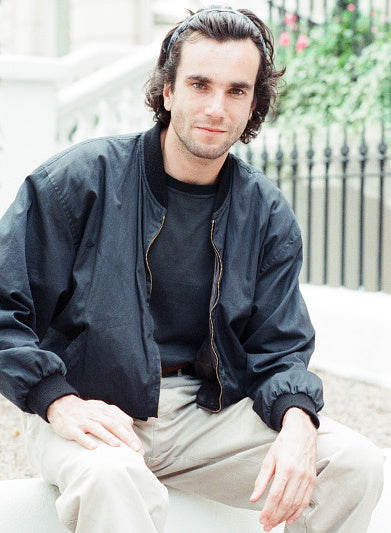

Daniel Day-Lewis has vanished. No more movies, no more public appearances. Not even any rumors. Although plenty of people thought the 2017 announcement of his retirement from acting was a passing whim that would not last, few now hold out hope for his return to the stage or screen. The only actor to have ever won three Oscars for best actor – in 1990 for My Left Foot, in 2008 for There Will Be Blood and in 2013 for Lincoln – he is known for his lack of interest in fame and the glittering social occasions that go with it, and seems to have chosen anonymity for good.

The last public images of the actor date back almost three years. In them, Day-Lewis walks through the streets of New York wearing a Carhartt Detroit jacket with a chambray shirt, carpenter pants recognizable by a side loop (to hang tools on), and a pair of work boots. In other photos, taken on the sly by a paparazzo, the actor is sitting in Central Park absently looking at his phone, drinking water and daydreaming. The carpenter pants have been replaced by a pair of Carhartt duck canvas double-knee pants and the chambray shirt by a flannel version – as though the actor had already found the costumes for his new role.

Day-Lewis, now 63, has always given his attire a central role in his life, slipping into his costumes like a second skin and letting film spill over into reality, sometimes to the point where the line between art and life blurs. In 1992, Day-Lewis was preparing to shoot The Age of Innocence, his first movie with Martin Scorsese and an adaptation of the Edith Wharton novel. To play Newland Archer, a high-society lawyer in late-19th-century New York, he read everything he could find on the lifestyle of the American upper-middle classes of the time. But his research didn’t stop there. For two months, Day-Lewis walked the streets of New York in the costumes that went with the role, including a cape, top hat and cane. “For me, it’s just part of the job,” he later explained.

SHOPPING IN LONDON

“I think Daniel needs to build up a character’s outward appearance and physical shape to develop the psychology of the role,” says Mark Bridges. “That’s how he works.” A renowned costume designer who won an Oscar in 2012 for his work on The Artist, Bridges first met Day-Lewis in 2007 on the set of There Will Be Blood. Their next encounter came a few years later with Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread, in which Day-Lewis plays Reynolds Woodcock, a haute couture dressmaker in 1950s London whose life is turned upside down when a new woman enters his life. “We began costume preparations two years before the shoot, which is a big step up from how it usually goes,” says Bridges. “Very quickly, we decided that the main inspiration was the figure of former British Prime Minister Anthony Eden, an imposing man who patronized Savile Row tailors. We listed everything we needed and then did a series of reconnaissance visits to the area. And Daniel was clearly calling the shots.”

He became a regular caller at George Cleverley, a prestigious bespoke shoemaker, for instance. “From 2015 onward, Daniel came to our Mayfair store on numerous occasions,” says Cleverley C.E.O. and Creative Director George Glasgow, Jr. “He’d delve into our archives, particularly the ones from the 1950s and ’60s, and then we’d have long discussions about leathers and shapes with our cordwainers [shoemakers].” Over the months, several pairs of boots were made for the film. They included suede models for the country scenes, when Woodcock is decked out in tweed, as well as a pair of black calf oxfords, the house’s absolute classic, which the actor wore to formal events. The collaboration was so successful that after one meeting, Day-Lewis ended up asking George Glasgow, Sr., the chairman, to be in the movie. The shoemaker played Nigel, Woodcock’s financial advisor, and even had a few lines of dialogue.

“After the shoes, there were pajamas from Budd, bow ties from Drake’s, hats from Lock & Co.,” says Bridges. These fittings and visits revealed to him the extent of Day-Lewis’s sartorial culture. “It was quite impressive. He could even talk technique with the tailors. I think Daniel was introduced to elegance at a very early age.”

The actor’s father was Cecil Day-Lewis, a famous English poet who died at the age of 68, when Daniel was only 15. An elegant man who regularly ordered clothes from the gentlemen’s outfitters of Savile Row, he predictably became an enduring model for his son and an endless source of inspiration. In real life, Daniel’s regular city wear includes a cable-knit fisherman’s sweater, a Gansey, which he had had copied from his father’s favorite design and hand-knitted in the northeast of England. “During fittings, he often brought up childhood memories,” Bridges says. “He’d tell us, with a great deal of emotion, about what his father and his friends used to wear.”

One day, at the tailors Anderson & Sheppard, the actor even took out an old photo of Cecil wearing a long coat with raglan sleeves. Daniel wanted the same garment for his character in the movie. The people at the illustrious tailoring store still remember the occasion. “He was very specific,” says Colin Heywood, managing director. “He suggested lots of fabrics, gorgeous materials he was familiar with. We worked on the designs together so they were in keeping with the period. High-waisted trousers, a single pleat, wide legs.” But Day-Lewis had another require- ment. “He also wanted us to ‘distress’ the pieces, so they wouldn’t look too new,” Heywood says. Day-Lewis finally took possession of the garments they’d ordered three weeks before the shoot – enough time to get into the skin of the character.

“We’re used to working with great actors, like Tom Hanks, [Robert] De Niro, Michael Caine,” says Glasgow, Jr. “But none of them work as hard as Day-Lewis to forge a character’s style.” Costume designer Bridges agrees: “I would say he pays more attention to detail than any other actor I’ve had the good fortune to work with.” When shooting began on Phantom Thread, Day-Lewis naturally continued his obsessive quest for perfection in every detail. In one of the movie’s crucial scenes, Woodcock’s wife surprises him with an impromptu dinner when he gets home from his daily walk. The dressmaker is distraught to have his routine disrupted but doesn’t dare refuse the invitation. Before sitting down to the meal, he goes off to change. “We hadn’t settled on anything specific for the scene,” Bridges says. “I let Daniel choose the outfit Woodcock would have put on at a mo- ment like that. The result was perfect; it told the story very well.” He returned in lavender pajamas under a sweater vest and green tweed checked jacket, offering a startling contrast tohis wife in her evening gown.

A COUTURE COURSE IN NEW YORK

As his short but pretty much flawless filmography shows, Day-Lewis is an actor like no other. He’s a dedicated, hard-working craftsman, a proponent of Method acting, the approach developed by Russian actor and director Konstantin Stanislavski in the early 20th century, which focuses on the power of experience and encourages actors to “live” in the skin of their characters when off the set. For each of his roles, Day-Lewis lived a different life. In 1989, while preparing for My Left Foot – the story of Christy Brown, a man with cerebral palsy who learned to paint with his left foot – Day-Lewis spent weeks in a wheelchair and asked to be spoon-fed to get as close as he could to the humiliations experienced by the real Christy. In 1993, for Jim Sheridan’s In the Name of the Father, he adopted a thick Northern Irish accent several weeks before filming; it took him weeks to get rid of it afterward. Nine years later, on the set of Gangs of New York, Day-Lewis gave Leonardo DiCaprio a scare between two scenes by sharpening his knife just the way his character, the madman Bill the Butcher, would have done.

Day-Lewis’s commitment to his role in Phantom Thread was fascinating. He wasn’t interested in looking like Reynolds Woodcock. Nor was he interested in dressing up like him. He wanted to be Reynolds Woodcock. But how? The actor decided he had to learn how to sew. “So, with Paul Thomas, the three of us decided to organize a course for Daniel to try his hand at it,” says Bridges. Starting in October 2015 and for more than a year, the actor spent several evenings a week with Marc Happel, director of costumes at the New York City Ballet. His mentor taught the actor how to hold a pin, take measurements, handle the heavy scissors that cut fabrics and manipulate mate- rials. Happel recalls with a smile: “I can still see it – the way he’d burst into my office every morning and immediately ask: ‘So, what are we doing today, Guv’nor?’”

The apprentice dressmaker learned fast. “I gave him exercises to do at home – embroi-dery, hand-stitched buttonholes – and the things he brought back were really beautiful,” Happel says. “He was like a sponge: he soaked it all up. One night, he showed me how well he could drape. I’ll never forget it!” In the end, these patiently learned couture gestures would be seen in only five scenes of the movie. “But it didn’t matter – those scenes were believable, and that was the most important thing,” Happel says. Day-Lewis himself never got to make that judgment. By the time the film was released, he no longer considered himself an actor and stubbornly refused to watch Phantom Thread.

MADE-TO-MEASURE SHOES IN FLORENCE

The Day-Lewis method is exceedingly successful, but it’s also grueling and all-consuming. “I’m constantly chasing ghosts, and that pursuit wears me out,” the actor confided to Le Monde’s M magazine in 2018. Day-Lewis had several nervous breakdowns during his career. One day in 1989, at the National Theatre in London, he left the stage right in the middle of a performance of Hamlet. “I’d become an empty shell,” he later explained. “I had nothing left in me, nothing to say, nothing to give.” He would never go back on stage again. The actor described the emotional turmoil he’s in by the end of a film as a “parched land where nothing grows back.” Before his retirement was announced in 2017, Day-Lewis had already put his career on hold. In 1996, he distanced himself and went off radar for almost five years.

On the advice of a friend, the Italian playwright Pier Paolo Pacini, Daniel Day-Lewis went to Florence in late 1999 to have a pair of shoes custom-made by the famous shoe- maker Stefano Bemer. “Stefano was an intelligent and sensitive man,” Pacini told the magazine So Film in 2013. “I thought it was an encounter that could work well and help Daniel.” Sure enough, in the tiny store nestled on a narrow street of the city’s less-upmarket left bank, when the British actor sat down in a leather armchair, he was touched by the simplicity of the man he met. “Stefano didn’t care if you were famous or not – he treated all his customers the same,” says Tommaso Melani, who knew Bemer well before taking the reins at the house after his death in 2012.

Three weeks after this first meeting with Bemer, Day-Lewis returned to the store with an unusual request. He wanted to learn the cordwainer’s trade. Bemer warned him that he had no money to pay him and that it would take time. Money was no object, and Day-Lewis had plenty of time. Exhausted after his last movie, The Boxer, and hounded by gossip magazines over his love life – his breakup with Isabelle Adjani, romantic relationship with Madonna, more or less proven affairs with Julia Roberts and Winona Ryder, and marriage to playwright Arthur Miller’s daughter Rebecca Miller – Day- Lewis needed a break. “He wanted to immerse himself in something else, to recharge his bat- teries,” says Melani. The Oscar-winning actor discovered a new profession, a manual trade like the ones he had dreamed of before he was offered a minor role in the film Sunday Bloody Sunday at the age of 14. In Florence, Day-Lewis worked hard five days a week: first in, last to leave. “Stefano taught him in his own way: you’re given a task, you keep doing it, you learn by practicing and observing,” Melani says.

The long, quiet, routine days suited the actor perfectly. Daniel Day-Lewis and Bemer became friends, even calling each other up in the middle of the night for a chat. For almost nine months, the actor pursued his appren- ticeship in the dusty 50-square-foot workshop, in company with the maestro and his three other shoemakers, all Japanese.

“Stefano and Daniel shared the same obsessive need for perfection,” says the current owner of the Florentine brand. “Daniel also took his apprenticeship quite far. He chose a complicated model to get his hand in, a burgundy calfskin Derby with a square toe and a shark apron. The pair was almost finished when he left.” But after nine months, Martin Scorsese came knocking on the workshop door. The movie director was working on Gangs of New York and had crossed the Atlantic to ask the fledgling cordwainer to become one of his heroes. After five days of pestering, Day-Lewis finally gave in and said yes to Scorsese. He was an actor again. For a few years...